It’s been a while, dear readers :)

For everyone who has stuck around in the nosebleed seats during this past (I’m calling it a Sabbatical, much more fun) – thank you! Between switching programs, final exams, grading papers, moving to a new home, and a long-overdue family trip, there has been no time for the writing desk. You will never know how much your support and readership mean to me.

To all the writers who keep up with their Substack despite the things I mentioned above — I salute you 🫡

And now onto the good stuff! 💎

Fancy French Words

The terms Champlevé and Cloisonné refer to two distinct enameling techniques that have been used for the production of precious objects since antiquity. While there are several techniques and notable schools, we are going to concentrate on these two for simplicity’s sake and also because they’re simply awesome.

These techniques (the big Cs) are two of the most important, widespread, and are still being used by many contemporary jewelers. In a nutshell:

Champlevé is a decorative technique that involves cutting away troughs or cells in a metal surface and filling them with pulverized vitreous (glass) enamel through the application of heat.1

Cloisonné is a technique for creating designs on metal vessels by placing colored-glass paste within compartments enclosed with hammered wire, known as cloisons (French for “cells” or “partitions”).2

The term ‘champlevé’ comes from the French for “raised field,” the ‘field’ being the uncut metal background. The oldest use of this technique can be seen in the Celtic art and jewelry created before and during the Roman occupation of Gaul (modern-day France), particularly in the Rhine River valley around Cologne and the Meuse River valley in Belgium. Early Celtic champlevé, known as La Tène style, consisted of heating the glass into a soft paste and pushing it into place, although this is more akin to glass inlay.

True champlevé — and what we still practice today — was learnt from the Romans (hello, glassmaking techniques!).3 This is when the glass is placed into position before being fired or heated and liquified into a paste.

Like its sister technique, cloisonné can be seen as far back as the ancient world with the Egyptians. Utilized mostly for small jewels and tomb objects, the Pectoral of Senusret II, from his daughter's grave, is a great example. I mean…just look at it (above). This pendant lives in my brain rent-free. While it uses inlaid stones rather than enamel, the gold partitions that make it cloisonné can be seen clearly. So, yes, it counts. This technique was also heavily used in Mycenae and Greece.4

Limoges & Beyond

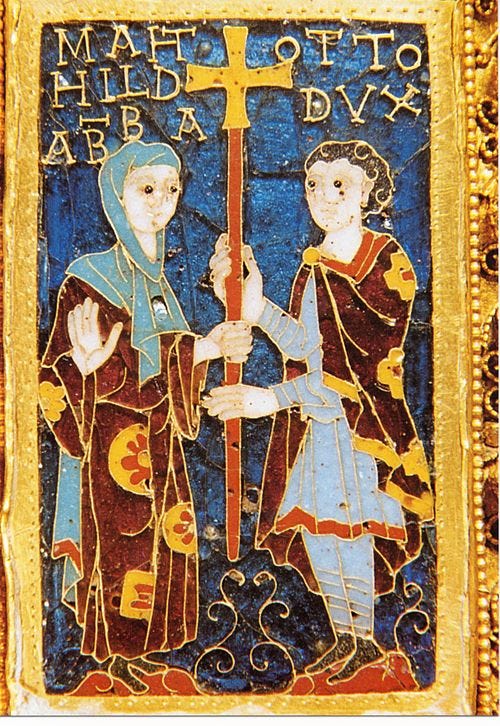

It wasn’t until the 11th and 12th centuries that these enamelling techniques exploded in popularity — hence our association of this ‘look’ with early Medieval art. Limoges (South-western France) is especially renowned for its use of champlevé enamel, dominating the industry in production from 1100 to 1370. It was established in the early 12th century when goldsmiths at the Benedictine Abbey of Conques in the ancient province of Rouergue began to create enamels “…whose jewel-like colors and rich, golden surfaces belied their fabrication from base copper.”5 By the 1160s, the enamels created at Limoges became known as opus lemovicense, a hallmark of the region.

Producing many beautiful reliquaries (containers for relics) and other precious religious objects, almost 8,000 pieces of Limoges enamelwork survive today. The majority of reliquaries are known as “chasse caskets” or box reliquaries in the shape of lovely houses or churches. These boxes would be richly decorated with inlaid gemstones or enamel decoration of religious figures and scenes. The fact that Limoges was one of the main pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain, likely helped (a lot) with distribution.6 Other objects include crucifixes, jewelry, vases, candlesticks, and manuscript covers, many of which exist all over Europe.

While Limoges certainly steals the show, these enamelling techniques can be found across cultures, with Chinese cloisonné becoming especially prominent during the Ming Dynasty (early 14th to 15th centuries).7 During this period, it was common to use cloisonné objects to furnish important temples, palaces, and aristocratic homes. This isn’t surprising given how beautiful these objects are! A glimpse at any of these foliated dishes and you’ll be wondering how these objects could ever be made by human hands!

Imported from the Islamic world into China via Yunnan under Mongol rule, these objects (dishes, vases, bottles, etc.) developed their own aesthetic and stylistic techniques, concentrating on floral patterns with bright colors.

Indian and Islamic objects also made great use of these techniques, with Limoges enamel exhibiting significant Islamic influence from an early stage in its production. The enamelling utilized in India, Iran, and Afghanistan is known as Meenakaari, a STUNNING and intricate decorative technique that uses enamel as paint, fusing the underlying metals with brilliant colors! Many examples include floral and avian patterns along with other animals on a floral background in electric colors like blue, green, yellow, and red. This art form, however, had been present in Iran since the time of the Parthians, with the meticulous ornamental work being developed in the 15th century. It spread to India during the Mughal Empire later in the 17th century, becoming a fundamental part of their cultural heritage.8

Enamelling reached its peak during the 18th and 19th centuries, with the likes of Fabergé, René Lalique, Tiffany and Co. producing some of the most beautiful decorative objects in art history. These include perfume bottles, lamps, jewelry, and many other objets d’art. These houses and artists pushed the boundaries of these inherited techniques and even developed new ones, such as guilloché and plique-à-jour. With such a long, rich, and varied history, it’s easy to see why enamel continues to be a beloved material to work with.

Not as long as I’d hoped it would be, but this bite-sized dive into the world of enamel is preferable to subjecting all of you to a thesis-length spiel on the subject. Either way, I hope you enjoyed reading, and it’s nice to be back!

xo Odette

If you enjoy my writing, please consider subscribing to have By Odette delivered to your inbox. Subscriptions are free! But if you’d like to support my writing, I’ve added a “Buy Me a Coffee” tip jar button below. No pressure, and thank you for reading!

Harvey Medill Higgins, Moira Gallagher, and Anne Grady, “Champlevé Enameling,” in Perspectives, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 24, 2022.

Department of Asian Art, “Chinese Cloisonné,” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

Susan Youngs (ed), “The Work of Angels,” Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th-9th centuries AD, 1989, British Museum Press, London.

GIA, “The Art of Enameling: The Techniques,” 2014.

Marie-Madeleine Gauthier, Bernadette Barriere, Dom Jean Becquet, et al., Enamels of Limoges, 1100–1350, MetPublications, 1996.

Internet Archive, “Hermitage exhibition,” St Petersberg, 2009.

“Chinese Cloisonné,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

Pedro Moura Carvalho, “Enamel in the Islamic Lands,” In Williams, Haydn (ed.). Enamels of the world, 1700-2000: the Khalili collections. London: Khalili Family Trust, 2009.